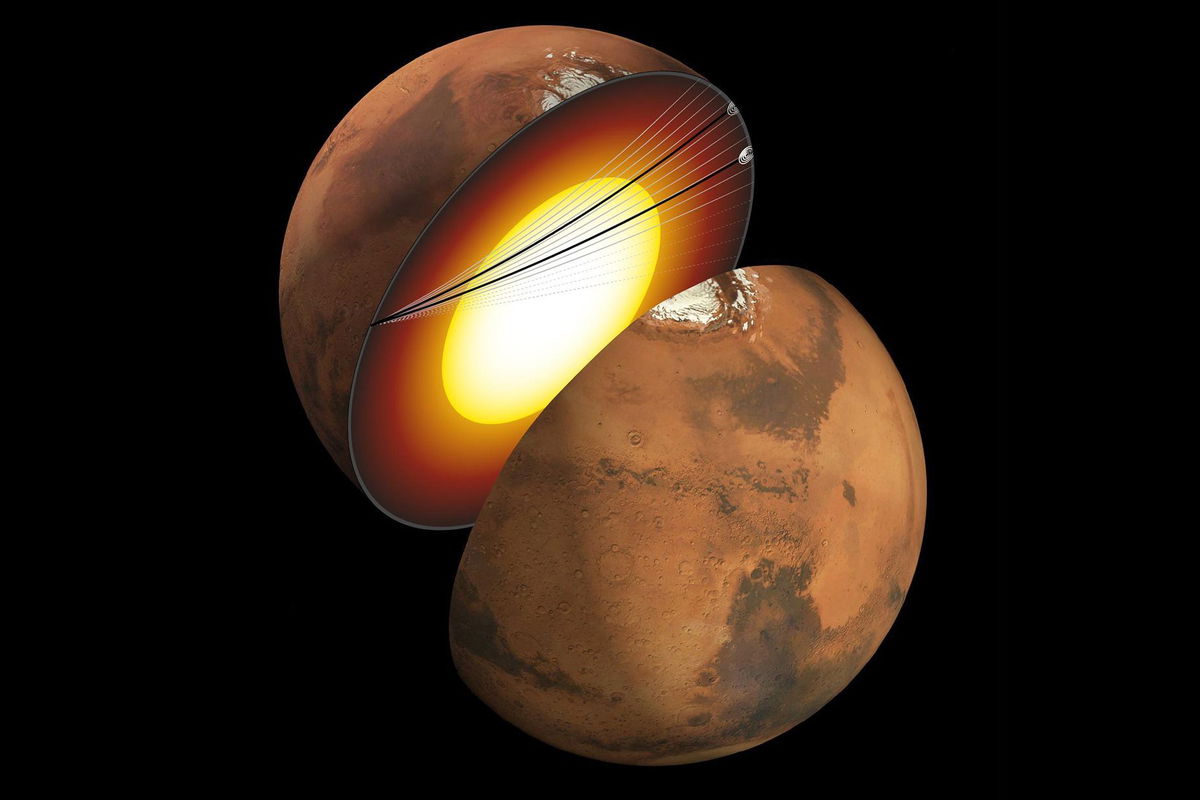

Recent research based on data from a retired NASA mission has unveiled a significant discovery: an underground reservoir of water deep beneath the Martian surface. According to the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists estimate that this groundwater, trapped in the rock’s tiny cracks and pores, could potentially fill oceans on Mars. The reservoir might cover the planet’s surface to a depth of approximately 1 mile (1.6 kilometers).

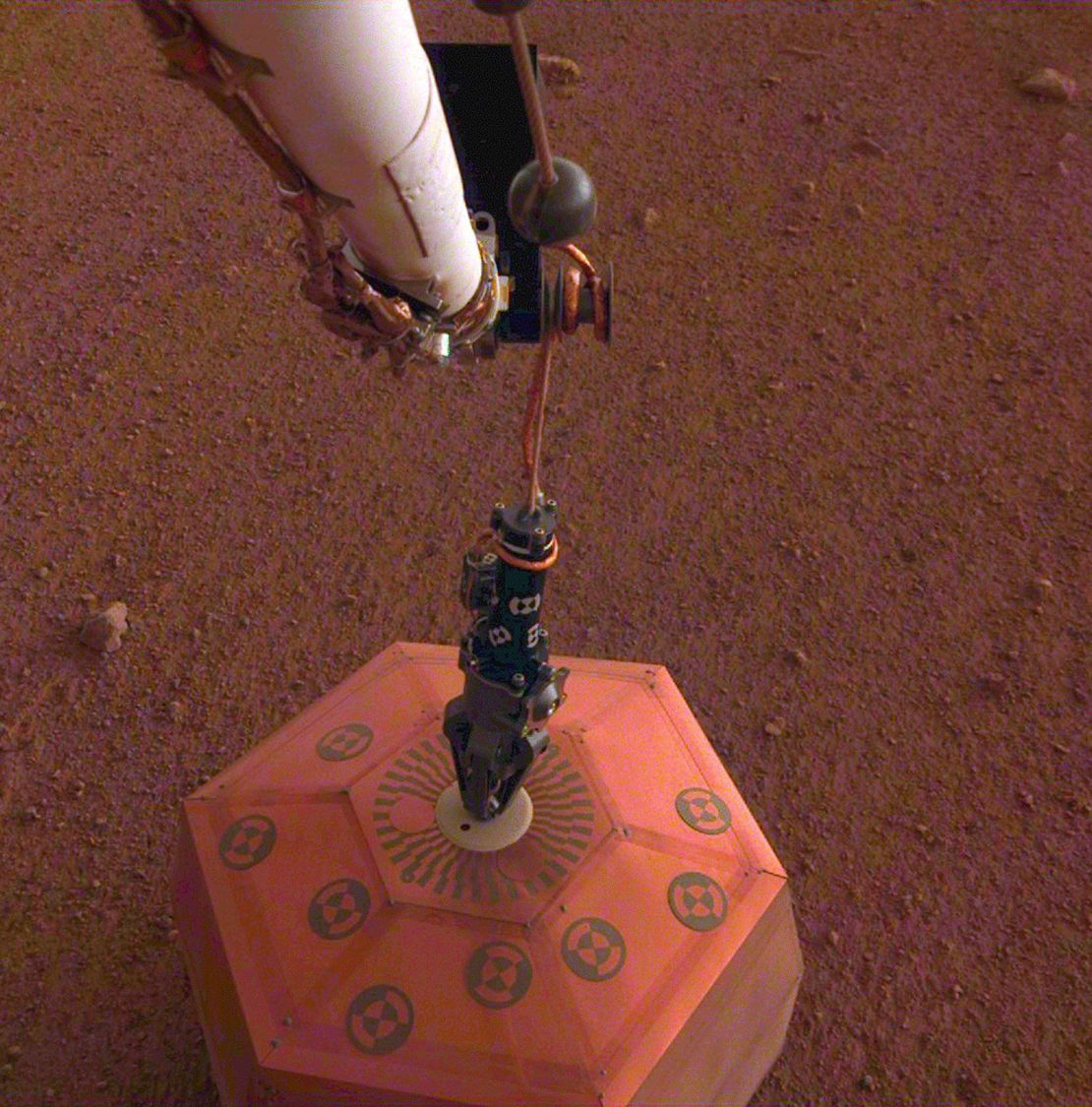

The data was collected by NASA’s InSight lander, which utilized a seismometer to probe Mars’s interior from 2018 to 2022. Despite being located between 7 and 12 miles (11.5 and 20 kilometers) beneath the surface, this newly discovered water reservoir presents intriguing possibilities for understanding Mars’s geological history and its potential for hosting life.

Lead study author Vashan Wright, an assistant professor and geophysicist at the University of California, San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, emphasized the importance of this discovery. “Understanding the Martian water cycle is critical for understanding the evolution of the climate, surface, and interior,” Wright stated. “A useful starting point is to identify where water is and how much is there.”

Mars was once a warmer, wetter planet, as evidenced by ancient lakes and river channels observed by previous NASA missions. However, the red planet lost its atmosphere over 3 billion years ago, ending this wet period. While some water remains trapped as ice at Mars’s polar caps, researchers have been investigating where the rest of the planet’s “lost” water went.

The new findings suggest that Mars’s water seeped into the planet’s crust. The InSight mission, which was stationary but collected extensive seismic data, revealed that Mars’s crust consists of a deep layer of igneous rock saturated with liquid water. This discovery could offer new insights into the planet’s climate and its potential to support life.

Study coauthor Michael Manga, a professor of earth and planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley, noted the implications of this finding. “And water is necessary for life as we know it. I don’t see why the underground reservoir is not a habitable environment,” Manga remarked.

The study also highlighted the challenge of accessing this water. Drilling to such depths on Mars would require substantial resources and technology. Despite these challenges, the discovery adds a new dimension to the ongoing search for life on Mars and the planet’s geological history.

While this research does not provide direct evidence of life on Mars, it suggests that the deep Martian crust could be a viable habitat for microbial life, much like the deep groundwater environments on Earth.

The findings mark a significant step forward in our understanding of Mars and its potential to harbor life, offering a promising avenue for future exploration and research.